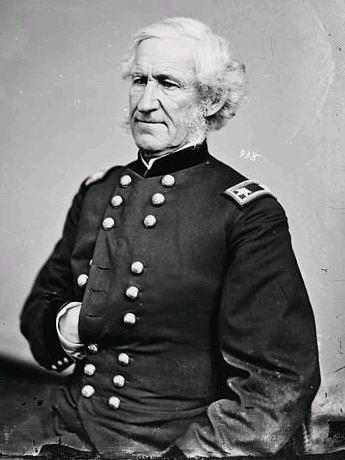

Lorenzo Thomas Seeks Officers for Colored Troops

In early April 1863, Adjutant General of the United States, Lorenzo Thomas, stopped at many of the posts along the Mississippi River and addressed the troops. His mission, authorized by the secretary of war as well as President Lincoln, was to declare the Administration’s policy and determination to enlist black men into the Union army. They would serve in segregated regiments (later known as the U.S. Colored Troops or USCTs), but would be officered by whites. Thomas addressed the veterans of Gen. John Logan’s Division, of McPherson’s Corps, on April 8. A reporter known as “Mack” from the Cincinnati Daily Commercial was there, and took down his speech:

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

From the Cincinnati Daily Commercial, Apr. 17, 1863:

As a speaker, General Thomas is not very highly gifted. He is not eloquent in word or manner, and must have a very interesting topic for discussion to hold the attention of his hearers. He spoke as follows, yesterday [April 8]:

General Thomas’ Speech.

FELLOW SOLDIERS – Your commanding general has so fully stated the object of my mission, it is almost unnecessary for me to say any thing to you in reference to it. Still, as I came here with full authority from the President of the United States to announce the policy which, after mature deliberation, has been determined upon by the wisdom of the nation, it is my duty to make known to you, clearly and fully, the features of this policy. It is a source of extreme gratification to me to come before you this day, knowing, as I do full well, how glorious have been your achievements in the field of battle. No soldier can come before soldiers of tried valor without having the deepest emotions of his soul stirred within him. These emotions I feel on the present occasion, and I beg you will listen to what I have to say as soldiers, receiving from a soldier the commands of the President of the United States.

I came from Washington clothed with the fullest power in this matter. With this power I can act precisely as if the President of the United States were himself present. I am directed to refer nothing to Washington, but to act promptly — what I have to do, to do at once — to strike down the unworthy and to elevate the deserving. I can only speak briefly, and can not enter into the details of this subject at present. It may be that some of you are better acquainted with this country than I am, but all my early military life was spent in the South. I know this whole region well. I am a southern man, and, if you will, born with southern prejudices, but I am free to say that the policy I am now to announce to you I indorse with my whole heart. You know full well, for you have been over this country — you know better than I do — that the rebels have sent into the field all of their available fighting men — every man capable of bearing arms — and you know they have kept at home all their slaves for the raising of subsistence for their armies in the field. In this way they can bring to bear against us all the strength of the so-called Confederate States, while we at the North can only send a portion of our fighting force, being compelled to leave behind another portion to cultivate our fields and supply the wants of an immense army.

The administration has determined to take from the rebels a source of supply — to take their negroes and compel them to send back a portion of their whites to cultivate their deserted plantations — and very poor persons they would be to fill the place of the dark-hued laborer. They must do this, or their armies will starve.

You know perfectly well that the rebels had an opportunity afforded them under the proclamation of the President on September last, to throw down their arms and come back into the Union. They failed to do it — not but that the hearts of many men of the South were with us and against the rebellion, but the leaders of the conspiracy, Jeff. Davis & Co., would not permit it; therefore, they are still in arms against us.

On the first day of January last, the President issued his proclamation declaring that, from that day forward, all of the slaves in the States then in rebellion, should be free[.] You know that vast numbers of these slaves are within your border — inside the lines of this army. They come into your camps, and you can not but receive them — you must receive them. The authorities at Washington are very much pained to hear, and I fear with truth in many cases, that some of this unfortunate race has, on different occasions, been turned away from us, and their applications for admission within our lines been refused by our officers and soldiers. This is not the way to use freed men.

The question came up in Washington: What is best to be done with this unfortunate race? They are crowding upon us in such numbers that some provision must be made for them. You can not send them North. You all know the prejudices of the Northern States against receiving large numbers of the colored race. Some States have passed laws prohibiting them to come within their borders. At this day, in some states, persons who have brought them have been arraigned before the courts to answer for the violation of State enactments.

Look along this river, and see the multitude of deserted plantations on its borders. These are the places for these freed men — where they can be self-sustaining, self-supporting.

All of you will some day be on picket duty, and I charge you all, if any of this unfortunate race come into your lines, that you do not turn them away, but receive them kindly and cordially. They are to be encouraged to come to us. They are to be received with open arms. They are to be fed and clothed. They are to be armed. This is the policy which has been fully determined upon. I am here to say that I am authorized to raise as many regiments of blacks as I can. I am authorized to give commissions, from the highest to the lowest, and I desire those persons who are earnest in this work to take hold of it. I desire only those whose hearts are in the work, and to those only will I give commissions. I don’t care who they are, or what their present rank may be, I do not hesitate to say that all proper persons will receive commissions.

While I am authorized thus in the name of the Secretary of War, I have the fullest authority to dismiss from the army any man, be his rank what it may, whom I find m[a]ltreating this unfortunate race. This part of my duty I will most assuredly perform, if any case comes before me. I would rather do that than to give commissions, because such men are unworthy the name of soldiers.

I hope to hear that in this large, this splendid division, as I know it to be — veterans, as Napoleon would call them for you are veterans — I hope to hear before I leave that I shall be able to raise at least a regiment from among you. I do not want to stop at one, nor at two. I must have two. I have two from the division below, at Lake Providence; more than two. I would like to raise on this river twenty regiments, at least, before I go back. I shall take all the women and children, and all the men unfit to become part of our military organization, and place them on these plantations; then take these regiments and put them in the rear. They will guard the rear effectually. Knowing the country well, familiar with all the roads and swamps, they will be able to track out the accursed guerrillas, and drive them from the land. When I get regiments raised in this way, you may sweep out into the interior as far as you like. Recollect therefore every regiment of blacks I raise, I release a regiment of whites to face the foe in the field. This, fellow soldiers, is the determined policy of the Administration. You all know full well when the President of the United States, ([t]hough he is said to be slow in coming to a determination,) when he once puts his foot down, it is there, and he is not going to take it up. He has put his foot down. I am here to assure you that my official influence will be given, that he shall not raise it.

Other Speeches.

At the conclusion of General Thomas’ speech, the troops made a loud call for General Logan, who was present. The general took the rostrum and made an excellent speech, full of patriotic fire and spirit. He indorsed the policy indicated by General Thomas, as he would indorse any policy having for its aim the suppression of the rebellion. He urged his men to give a hearty support to it.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

David Cornwell, a private in Battery D, 1st Illinois Light Artillery, agreed with “Mack’s” assessment of Thomas’s speech. The general was a poor orator, and the introduction by corps commander Gen. James B. McPherson did an effective job of outlining the main points of Thomas’s visit. Thomas, therefore, was left with nothing to do but to reiterate what the soldiers had already heard – as he was charged with making the formal and official announcement of the new policy to organize black regiments. Thomas was followed by Gen. John Logan, who, in Cornwell’s words, “delivered a rattling ten minute speech.” It was enough to convince Cornwell and many others. He would soon become a lieutenant in one of the new regiments.

Source for Cornwell: The Cornwell Chronicles: Tales of an American life on the Erie Canal, building Chicago, in the Volunteer Civil War Western Army, on the farm, in the country store , p.187.

Comments

Lorenzo Thomas Seeks Officers for Colored Troops — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>