Gunboat casualties at Milliken’s Bend

How many men died or were wounded by shells from the Union gunboats Choctaw and Lexington? I did not have a ready answer to this question when it was posed to me at the Litchfield MN Civil War Round Table, so I wanted to try to find out more.

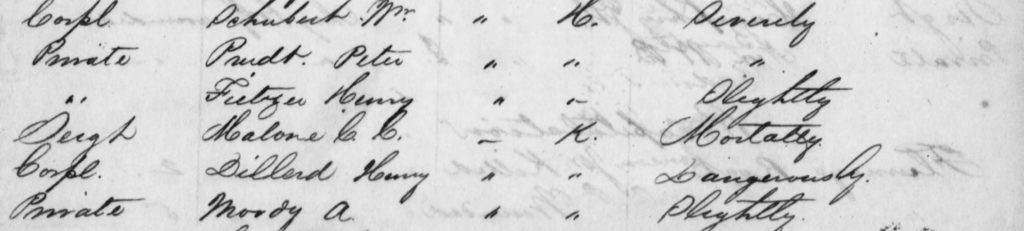

The Confederate regiment likely to have sustained the greatest gunboat casualties, due to their position on the battlefield, was the 16th Texas Cavalry, who were fighting on foot as infantry, having been permanently dismounted in 1862. However, their casualty list shows only the severity of the wound (“slightly,” “mortally,” and so on) – not what caused the wound or where on the body the soldier was injured. Such reporting was also the case with both the 17th Texas Infantry and the 19th Texas Infantry.

The casualty list for Col. Flournoy’s 16th Texas Infantry provides more detail, but only one injury seems able to be attributed to a gunboat shell, that of Frank Parsley in Company E, who was injured by a “bomb.”

Most of the gunboats’ fire was highly inaccurate, with many shells going over the assaulting troops’ heads. D. E. Young of the 17th Texas reported they “throde shell and shot at us too but tha dun no damege to us tha kill too men.” So it is not clear how many Confederate casualties were the result of gunboat artillery, but it seems likely it was only a fraction of the whole.

The Union side, too, suffered a few casualties – or at minimum, unexpected danger – from their own gunboats when shells fell short. The commander of the Choctaw, Lt. Cmdr. Frank M. Ramsey noted in his log: “Every one of our 5-second shells commenced turning over as soon as it left the gun.” Ironically, shells captured from the Confederates at Haynes’ Bluff fired true, with no problems. Lt. Col. Cyrus Sears of the 11th Louisiana Infantry, African Descent, complained about the short shells, and hospital records show that at least one man from 9th Louisiana Infantry, A.D., Charles Evans, was wounded in the spine by a shell, and paralyzed. He died about two weeks later on June 24.

No solid numbers can be obtained about the number of gunboat casualties sustained by the combat forces on land, but it seems likely based on these incidental reports that perhaps no more than 10 men – out of a total of 535 killed and wounded (175 CSA + 360 USA) – were victims of the intense shelling that put an end to the Confederate advance at Milliken’s Bend.

Sources: Milliken’s Bend: A Civil War Battle in History and Memory, p. 98, 100, 106, 204. “List of Killed, Wounded and Missing of Gen. H. E. McCulloch’s Brigade…Milliken’s Bend,” Fold3.com. National Archives: RG 94 Records of the Adjutant Generals Office, Entry 544, Field Records of Hospitals – Louisiana – v. 159.

Why I asked the question…you had stated the boats helped with the battle. But if no harm done, how could that be what slowed the Rebels down? If canister, I understand. But when records say not, makes me wonder even more.

Right. There are a couple of pieces to this, I think. First – and this is important from both sides – is that the Union gunboats were firing blind. The river level was down, and the main part of the battle was taking place on the other side of two levees. The gunners on the gunboats could not see their targets, and were having their fire directed by infantrymen on shore. The Choctaw arrived first, and was engaged the longest. Lexington came up later. In some accounts it also seems that some Rebel soldiers mistook the smoke stacks of the transport vessel that the 23rd Iowa was on for a gunboat. One reason McCulloch gave for his withdrawal was his anticipation that additional gunboats were on their way, and this may have been prompted by the Lexington arriving mid-way through the battle. Confederate General Richard Taylor saw McCulloch’s withdrawal as bordering on cowardice, writing that he had not seen such fear of gunboats since the beginning of the war.

As to the type of ammunition being used, it wasn’t canister. It seems to have been mostly shell. That would make sense as they’d need to have trajectory in their firing, in order to fire over the heads of their own men and the levees. Having shells bursting in air would rain down shrapnel on the troops below, without the need for specifically identifiable and visual targets.

I base my assessment of the gunboats halting the Confederate advance, in part, on McCulloch’s own report about the battle, and also on the basis that due to the collapse of the Union line, there really was nothing else to prevent the Confederates running all the Yankees into the river, quite literally. To be sure, the two companies of the 11th Louisiana on the far right of the Union line held their ground, and undoubtedly caused casualties, but I don’t think their stand alone would prompt a withdrawal. I think their efforts coupled with the gunboats’ fire is what made the Confederates pull back to await reinforcements.

Granted, the casualties caused by the gunboats may have been minimal, but I do think that the sheer mayhem of taking a prolonged shelling – esp. if the Rebs were kind of caught between two ranges of shells (ones falling behind them, firing long, and ones falling short in front of them, into Union lines) might have made them think it was only a matter of time before the gunboats found the right range.