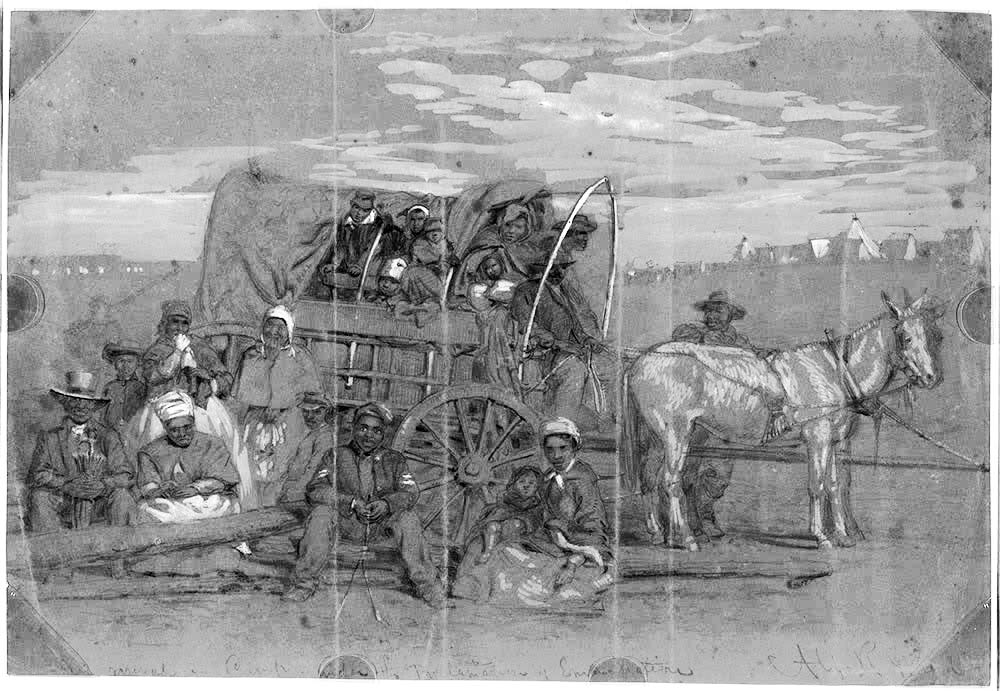

Contrabands: a new life of freedom or a return to slavery?

In 1861, at Fortress Monroe, Virginia, Union general Benjamin Butler refused to return three runaway slaves to their owners, even though Federal law required him to do so under the Fugitive Slave Act. Butler had a different take. Southern law and practice termed slaves as “property.” Butler, an attorney before the war, decided that as “property,” these men could be taken for use by the U.S. Army, just like any other type of property captured from the enemy. His shrewd calculation set a new precedent, later made official policy by the U.S. Congress when it passed the First (1861) and Second (1862) Confiscation Acts. Soon any black near Union lines was termed a “contraband”.

By late 1862, John Eaton, based in Memphis, was placed in command of numerous contraband camps located up and down the lower Mississippi Valley, dotting the landscape from Cairo, Illinois to Louisiana. Despite an attempt to organize the camps to provide essential aid to these men and women and their families, the first six months of the operations were only a marginal success. True, thousands of former slaves had flocked to Union lines, but the supplies necessary for this mass of people were completely inadequate. As General Grant prepared for the spring campaign and his move against Vicksburg, the army could not provide sufficient rations. Diseases spread rapidly in the camps, and few surgeons could be spared from the military. In one case, one doctor was tasked with the care of more than 2000 people. Initially, the contraband camps had been beacons of liberty, drawing the former slaves to what seemed a hopeful future, and freedom at last. But this mass exodus overwhelmed the Union military and civilian authorities, and the situation soon turned to one of great suffering.

By late spring 1863, matters began to escalate. Even more people were coming into the lines – at one place, nearly 100 a day. At Lake Providence, clothing was in such short supply some people were nearly naked. A charitable clothing donation from the North arrived just in the nick of time, but it was only enough to clothe those in greatest need. Much more would be necessary.

In April, a new system was devised to care for the freedpeople. Confiscated Southern plantations would be leased out to good Northern men, who would then hire workers selected from the contraband camps. Wages for men would be $7 a month; women would earn $5, probably comparable with general farm laborers elsewhere. There was a strict prohibition against children younger than 12 working in the fields. At first, the plantation leasing system seemed like a good idea. It would disperse the people from the unhealthy camps; put them to work for wages; help to grow their own food and possibly provide a surplus to the army; and enable them to take the first steps towards freedom by working on their own account.

But a short time afterward, Union general John P. Hawkins wrote to abolitionist Gerrit Smith that plantation lessees suffered from the same blindness that their slaveholding predecessors had: “cotton closes their eyes to justice just as it did in the case of the former slave masters.” Freedmen began running away from the plantation, again. Some, it was said, chose to return to their old masters. A newspaper reporter from Cincinnati saw the problem of plantation leasing clearly: “Call it by what name you will, it is nothing but a system of slavery.”

Comments

Contrabands: a new life of freedom or a return to slavery? — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>